Since the beginning of the 21st century, a flurry of cultural activity has emerged from a certain location on the borderlands of the intellectual landscape. Its points of view are fueled by a distinctly blurred range of influences. These include psychogeography and hauntology, with the occasional influx of Situationist or surrealist sympathies. Although approached from radically different angles, the works created by those operating within this zone—whether literary, cinematic, visual, or musical—tend to fluctuate between the twin poles of fascination with the urban on the one hand and the rural and folkloric on the other, ultimately resolving within the liminal space that lies between the two. But it is within that liminal space—in which brutalist architecture, beat poetry, public information films, ancient village traditions, forgotten library LPs, surrealism, standing stones, 1970s children’s television, pulp paperbacks, and obscure figures from the history of the occult are all treated with equal weight and reverence—that the zeitgeist truly reveals itself.

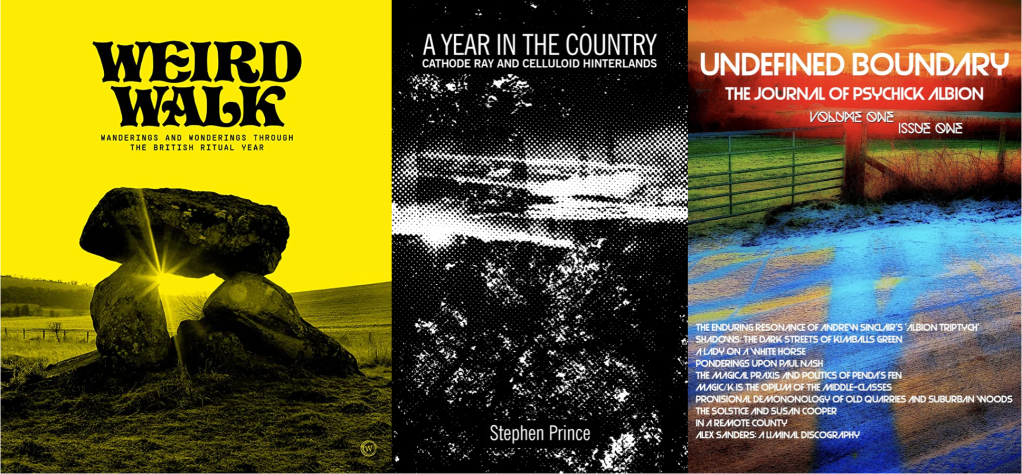

This is a trend that defies easy labels, with most activity being found in the blogosphere and in DIY releases. It finds its voice in zines like Weird Walk, blogs like Stephen Prince’s A Year in the Country, and the output of small publishers like Wyrd Harvest Press or Cormac Pentecost’s Temporal Boundary Press. But what is the point of all this enthusiasm for the forgotten corners of landscape, microhistory, and popular culture? The participants in this milieu are all engaged at some level in poiesis: a creative process, an action that can transform how we see reality. Often present in their works is the attempt to uncover hidden meanings and occulted connections in the otherwise mundane. At times these exercises in avant-garde antiquarianism, hermeneutical urban planning, and occultural archaeology feel like nothing short of an attempt to create a new mythology.

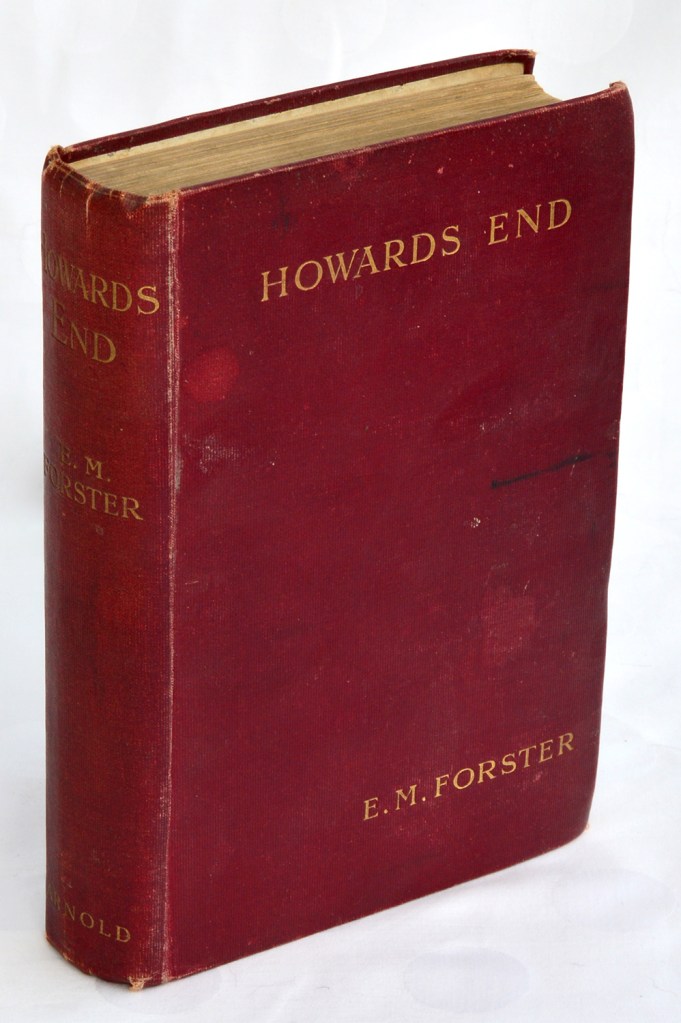

In E. M. Forster’s 1910 novel Howards End there is a scene in which a character begins musing on local legends and their larger meaning while walking across a village green in rural Hertfordshire:

“Why has not England a great mythology? Our folklore has never advanced beyond daintiness, and the greater melodies about our countryside have all issued through the pipes of Greece. Deep and true as the native imagination can be, it seems to have failed here. It has stopped with the witches and the fairies. It cannot vivify one fraction of a summer field, or give names to half a dozen stars. England still waits for the supreme moment of her literature—for the great poet who shall voice her, or better still for the thousand little poets whose voices shall pass into our common talk.”

The character is named Margaret Schlegel. Although educated and well read, she seems to have missed that England’s great poet, the “supreme moment of her literature,” may well have already arrived a century before, in the form of William Blake. Although still sometimes cast as a madman at the time, by 1910 Blake had been rediscovered and a reappreciation of his life and work was in full flower. Also that year, a veritable army of folklorists had already for decades been delving deeply into the island’s folk culture in an attempt to unveil and document England’s “great mythology,” finding it anything but “dainty.” The collected publications of scholars like Alfred Nutt, Jessie L. Weston, and Sir James George Frazer suggested that Britain very much had its own rich mythology that went far beyond nursery tales of enchanted woodlands. Perhaps, though, she had in mind something less fragmented, something that could be served up readymade: a national myth cycle like Finland’s Kalevala or Wagner’s crafting of the Ring cycle into a mythology that a newly-unified Germany could claim as its own.

Despite these apparent blind spots, Margaret’s call for a “thousand little poets” seems almost prophetic, perfectly capturing the creative landscape of the early 21st century in which scores of inventive minds strive diligently, if somewhat obliquely, towards reworking a moribund mythology into something both ethical and relevant to modern society—a new mythology that deals not only with witches and fairies, but also with capitalism, class, identity, and race. Although this trend began in Britain and a number of its threads are decidedly Anglocentric, many of these modern creative minds are no longer content to simply solve the Problem of England—to borrow a phrase from Patrick Keiller—but seem to be seeking new ways to frame the Problem of Modern Existence at its most fundamental level.

Although Margaret Schlegel and her siblings were portrayed in Forster’s novel as being “English to the backbone,” their father was German. He was said to have “belonged to a type that was more prominent in Germany fifty years ago than now. . . .If one classed him at all it would be as the countryman of Hegel and Kant, as the idealist, inclined to be dreamy, whose Imperialism was the Imperialism of the air.” Forster’s choice of surname for this family was unlikely to have been an accident. At the beginning of the 19th century, the very same moment that Blake was delivering his own half-mad vision to the world, the German romantic philosopher Friedrich Schlegel was calling for the creation of a new mythology, one that would unlock humankind’s “divinatory power.” In his article “Filling the Black(w)hole: The Call for a New Mythology by the German Romantics and Its Reach into the Digital Age,” scholar Nathan Bates asks, “But how could such a mythology be created?” He answers this by saying that “a solution would be best achieved, according to Schlegel, by individual creative efforts.”

Of course, what is meant here by mythology is not simply fairy stories, but something closer to Joseph Campbell’s concept of myth as the ongoing search for “the experience of life.” This is the very thing that has occupied philosophers, psychologists, and theologians for millennia, the search for those fundamental elements within our psychic depths that serve as anchor and fulcrum in the creation of our metaphysics, our cosmology. Myth is the form those elements take when they cross the proscenium from the abstracted world of the subconscious and emerge into the part of the mind that engages with the physical world. From there they reveal themselves—subtly, often unrecognizably—translated into cultural expression. This expression includes the whole gamut of human endeavor: art, architecture, music, literature, cartography, design, urban planning, and much more, in both their “high” and vernacular forms.

The most exemplary contemporary expression of this tendency in both its breadth and depth is perhaps Undefined Boundary: The Journal of Psychick Albion, the latest imprint from Temporal Boundary Press. In the introduction to the second issue, editor and founder Cormac Pentecost writes: “The defining feature of all things Psychick Albion is the question of whether reality contains something more than we suspect. Artists of all persuasions are intimately in touch with this question because their work involves imagination and creativity; they are working to bring new worlds into being. . . .There is a tacit agreement between writer and reader that we will allow the possibility of this other reality to hang in the air, perhaps as an illusory image of something eternally true, perhaps as a simple fiction, but in any case as a possibility. This is the key: not to interrogate the ontological status of this other state of being, but to explore it for the lessons it can bring us about how to most creatively live our lives.”

In his essay “A Lady on a White Horse” in the first issue of the journal, Nigel Wilson explores the folklore surrounding this figure, through her pagan, Roman, and Christian-era manifestations. He closes his piece by casting the modern era as one in which it has “become difficult to dream.” The current era is one in which “the emphasis is for leaders, preferably a strong authoritative one who is beyond contradiction; a person to whom we are all subordinate: the hero, the genius, the Great Leader. Let us call this the Age of the Father.” He then goes on to reject this worldview and to make a statement that could easily be interpreted as a call for a new mythology: “. . . but let us also be aware that this age may now be approaching the point where such stern figures have become redundant to human need for the simple reason that they don’t make sense anymore. What is required is more cooperation, more collective decision making.”

In the journal’s second issue, in his article “The Spectre of Trauma in the Myth of Psychick Albion,” George Parr is even more specific in his call for a new paradigm: “The suggestion then, is that through piecing together these lost threads we might find an alternative Britain in which the pastoral alchemy and gothic psychedelia of the island’s rich and diverse countryside may no longer be a quaint trend subtly running through our traditions and art, but at the very forefront of our culture. A Britain where Tory aristocracy is not the norm, where the spirit of anarchic magic and rebellious art are the guiding principles—a Psychick Albion in place of a Great Britain.”

In responding naturally to the various fascinations that propel them along their various trajectories, the collective work of these “thousand little poets” reveals that whatever vestiges of traditional myth remain in Anglophone cultures are often woefully inadequate for the spiritual, intellectual, and material circumstances in which we now find ourselves. To be clear, I don’t mean to imply that this search for a new mythology is necessarily a conscious pursuit. As Joseph Campbell stated in his famous 1988 television interview with journalist Bill Moyers, “You can’t predict what myth is going to be any more than you can predict what you’re going to dream tonight. Myths and dreams come from the same place.”

—Stephen Canner