“The end of a millennium promises apocalypse and revelation. But at the close of the twentieth century the golden age seems behind us, not ahead. The endgame of the 1990s promises neither nirvana nor Armageddon, but entropy.” In Robert Hewison’s Future Tense: A New Art for the Nineties, published in 1990, he paints a world in which the avant-garde has been fetishized and commodified until it has been stripped of all relevance. He describes a cultural stagnation that he associates with postmodernism, and in so doing anticipates Mark Fisher’s ideas of “lost futures” by nearly a quarter century, although both drew heavily on the foundational work of Frederic Jameson in this area.

Hewison does not believe that all is lost, however. In Future Tense he surveys a number of artists and writers who were actively bucking the negative inertia of the time in an attempt to “break through the screen of cultural conservatism and commercial Philistinism to challenge official values and offer a passionate vision of future possibilities.” In a contemporary review of the book for The Observer, Mik Flood states that Hewison’s focus is on those who “have been burnt out, wiped out, priced out or sucked out by the hegemonic monoculture of the corporate marketplace.” Hewison does not limit his study to the plastic arts, but includes actors, performance artists, architects, and writers. To explore British literature’s response to this cultural malaise, he discusses three novels: Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor (1985), Iain Sinclair’s White Chappell: Scarlet Tracings (1987), and Michael Moorcock’s Mother London (1988).

To me there is something prescient about choosing to focus on these three novelists as a group as early as 1990. Ackroyd and Sinclair were poets who had only been writing fiction for a very short time. There was not yet much, if any, buzz about the shared themes that these writers are now known for, which often seems to boil down to history and antiquarianism practiced as an occult art. Most strikingly, in his introduction Hewison states that he has used these three novels, along with the London scenes from Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, “to evoke an idea of the city—what the Situationists called a ‘psychogeography’—that is more profound than planners’ plot ratios.” This is certainly one of the earliest associations of psychogeography with these London writers to ever appear in print.

Although all three of these novels take place in and around London, what they share at a deeper level is a unique vision of time and how it functions. In Hawksmoor, Peter Ackroyd replaces the historical architect Nicholas Hawksmoor—who flourished in the early 18th century and is best known for the six London churches he designed—with the fictional Nicholas Dyer, a worshipper of Satan with some very unorthodox ideas about architecture. Hawksmoor himself is transmuted into a 20th-century detective charged with solving a series of murders that have occurred near each of Dyer’s churches. The connections and interactions between the two narratives, separated by nearly 300 years in time, drive the plot.

Ackroyd borrowed—or stole, depending on your point of view— the idea of occult associations with Nicholas Hawksmoor’s designs directly from Iain Sinclair’s 1975 poetic work Lud Heat. In a 1996 article in the London Review of Books, Sinclair describes Ackroyd in a sort of sideways compliment as “an unparalleled library vampire, a gutter and filleter of texts, a master of synthesis.” Hewison’s analysis of Sinclair’s first novel, White Chappell: Scarlet Tracings goes deep. He calls it “a multi-layered scrapheap of literary, historical and autobiographical references, where characters move back and forth in time, and narrative is broken and collaged into a pattern that matches the dissociated experience of the twentieth-century narrator, yet nonetheless is directed towards a transcendental unity.”

Time, not geography, again becomes the most important element in Hewison’s discussion of the novel. To highlight this aspect, he quotes from the text at some length: “We have got to imagine some stupendous whole wherein all that has ever come into being or will come co-exists. . . . So it’s all there in the breath of the stones. There is a geology of time! We can take the bricks into our hands: as we grasp them, we enter it. The dead moment only as we live it now. No shadows across the landscape of the past—we have what is coming: we arrive at what was, and we make it now.”

Already, at this early date, Hewison seems to deeply understand Sinclair’s approach: “The invitation is to decipher White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings as a prophetic text: its construction suggests further breakdown and dislocation, but it also shows that the experience of the city cannot be limited to the present, nor can the past be confined to museums. The ‘geology of time’ is such that, if we will allow them, the resonances of the past can inform contemporary existence without having to be turned into the simulacra of tourism.” This quote also evinces an understanding of Sinclair’s methodology that would inform his later non-fiction, but would not become well known until the publication of Lights Out for the Territory: 9 Excursions in the Secret History of London in 1997.

In both White Chappell: Scarlet Tracings and in Michael Moorcock’s Mother London, the “city becomes a form of collective unconscious” according to Hewison. The latter novel’s cast of characters is made up of a group of outpatients from a mental hospital, all having suffered various traumas during the Blitz. The narrative “moves forward and back in time between 1940 and the 1980s, weaving a pattern of experience and memory that presents an image of London’s deep imaginative resources.” It includes a character named David Mummery who has written a book called London’s Hidden Burial Grounds and is working on a new one on the city’s “lost” tube lines. While researching this new book, he discovers that “there are, too, older tunnels, begun for a variety of reasons, some of which run under the river, some of which form passages between buildings. . . . Others had hinted at a London under London in a variety of texts from as far back as Chaucer.” Setting aside the fact that Richard Trench and Ellis Hillman’s London Under London: A Subterranean Guide had already appeared in 1984, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that Moorcock just may have had his friend Iain Sinclair in mind when developing this character.

Hewison ends this section of the book by stating, “These novels depict the city ‘visible but unseen’ of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. But to reveal the many layers, the psychic archaeology of the city, it is necessary to abandon mere surface realism. Time has to be presented free of conventional perspective, the present of every moment is disrupted by the knowledge of, even intervention by other moments. Narrative is as fragmentary as experience, and mysteries are not explained.”

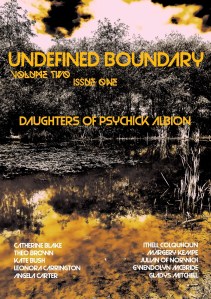

This idea of “psychic archaeology” feels to me like the perfect term to describe the approach of many of those 21st-century writers and artists who have been heavily influenced, directly or indirectly, by the early work of Ackroyd, Sinclair, and Moorcock. As examples, I think of the authors who appear in Undefined Boundary: The Journal of Psychick Albion or Andy Sharp and his English Heretic project. And like Hewison’s trio of London writers, those within this contemporary milieu are usually content to let the mysteries remain. There is no attempt to “solve” the world around us. There are simply suggestions as to how one might view reality with a different filter.

The concept of “London writers” that emerged around 1990 created an easily understood label around which their shared influences could congeal. At this early date Iain Sinclair was just beginning his transformation from avant-garde poet and book dealer into the Wizard of Hackney. His method of engaging with “mundane” reality as something almost magical would inform an entire subgenre of writing in the 21stcentury, one that would effectively become its own intellectual subculture. Acting as something of an alchemical reagent to allow this subculture to begin to grow in earnest, the newsletters of the London Psychogeographical Association first appeared in 1993, drawing heavily on Sinclair’s work. While parodying the “Grand Narrative” approach that characterizes much pseudoscientific writing from the fringes, they created a model in which the occult, history, landscape, popular archaeology, political hegemony, and the effects of capitalism could be easily connected, providing something of a subliminal blueprint for many writers who were to follow.

The timing of Hewison’s book is important. Although many of its intellectual sources can be traced further back, the current 21st-century experimental cultural climate in which the importance of liminality, landscape, folklore, and the idea of occulted history are dominant themes first appeared as something recognizable around 1990. It emerged at the place where avant-garde poetry and art intersected with anarchist and Situationist ideas, often expressed in the language of the occult. In those early days it carried no easy labels, so researching its origins more deeply will likely require an adoption of its own methodology, looking for the traces, the resonances, the “psychic heat” its practitioners left behind them.

—Stephen Canner

Thanks for posting this!

My experience of practicing the dérive seems to be insular for the most part and so to apply aspects of psychogeography in an attempt to analyze the fictitious work of others can feel elusive to me.

It’s nice to read the words of someone who can navigate this terrain with a sense of poise.

LikeLike