In high school, I was never far away from my camera. I took two years of photography, became competent in the darkroom, and served as a photographer on the yearbook staff. By my early 20s, I’d moved to Bloomington to attend Indiana University, my interests were directed elsewhere, and photography had receded into a casual hobby.

One hot, lazy Sunday afternoon in the summer of 1985, I decided to walk around town and take a few pictures. I still had my old Minolta XG-7, likely loaded with a 36-exposure roll of Kodacolor VR 200 film. I am presuming it was a Sunday, because that was the one day of the week when I was free from both my restaurant job and my summer classes. In those days, Bloomington was something of a ghost town during the summer months. For those of us who lived there year-round, this was a welcome respite from the crowds of students that filled the sidewalks during the regular semesters.

My goal that day was to photograph my everyday surroundings and try to make them look interesting. I had no illusions that the results would amount to anything other than an experiment. The first picture I took was of an empty retail storefront on North Walnut that had only recently been vacated. The front window bore the remnants of a large, adhesive advertisement—partially removed, but still clearly depicting the iconic Marlboro Man, a cigarette in his mouth, a lariat and saddle thrown over his shoulder. Directly below this emblem of rugged masculinity, inside the shop, was a gumball machine, the sort once seen everywhere, raising pennies for the various charities supported by the Lions Club.

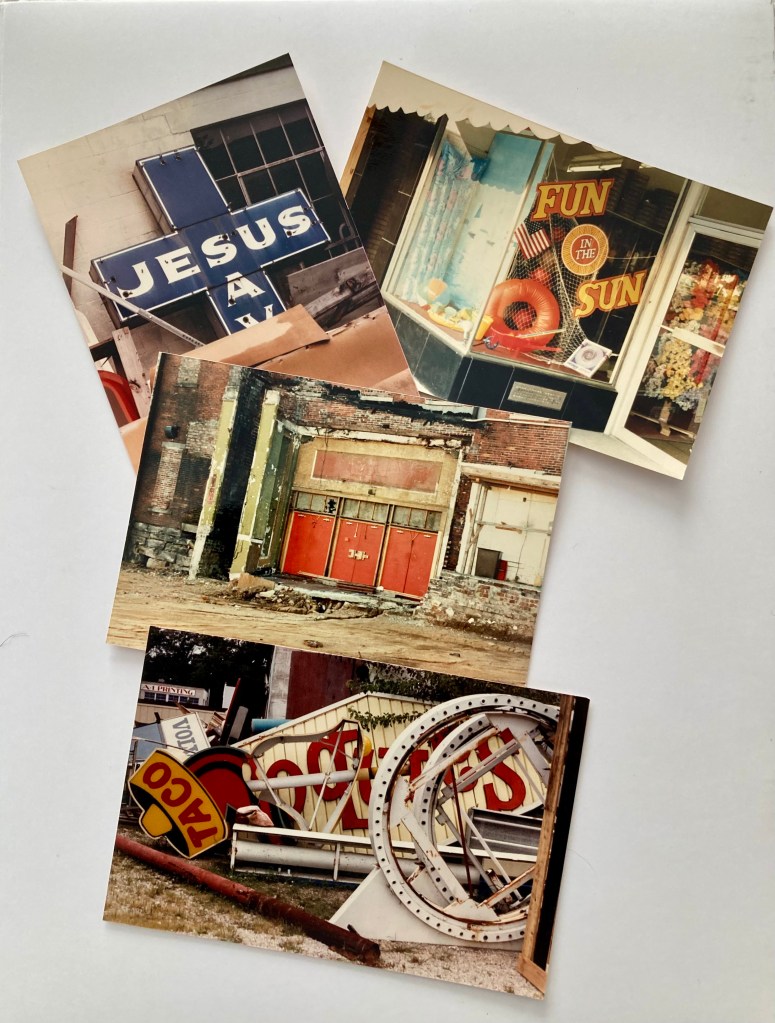

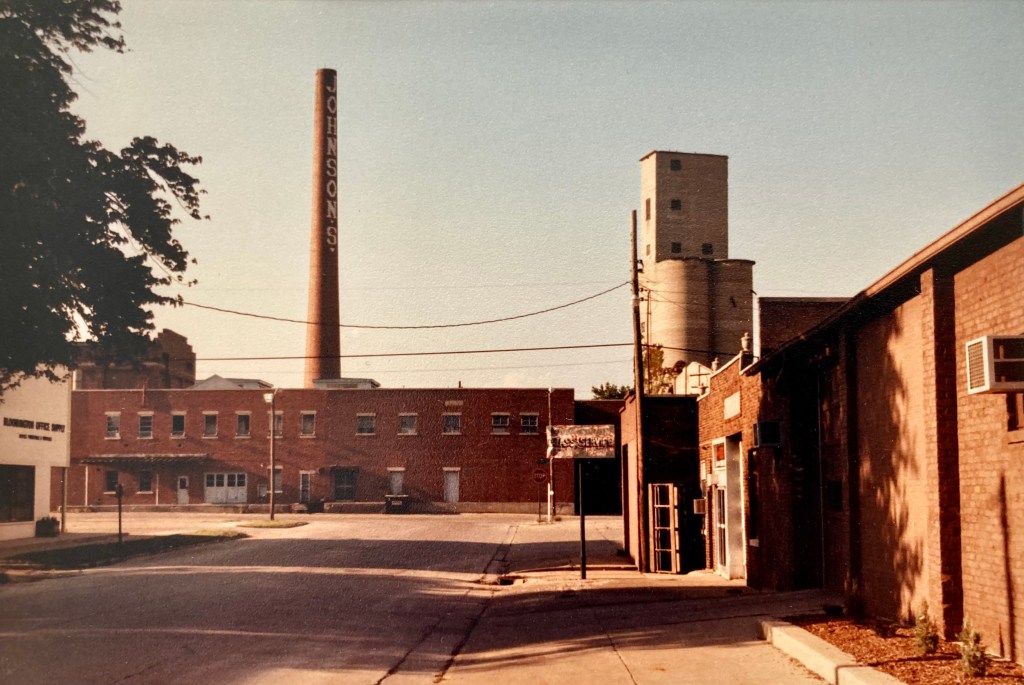

As I pressed the shutter release, I was struck by the small-town Americana vibe of this tableau. I also remember thinking, very clearly, that while most people would not find the image particularly interesting at that moment, it might be seen quite differently in forty or fifty years—a span of time difficult for me to even imagine at that age. I spent the next hour or two wandering central Bloomington, eventually exposing some twenty frames—a conservative number by today’s standards, but film processing was a luxury in those days on a college student’s budget. My subjects included the old Showers furniture factory, with garbage trucks lined up before it like hogs feeding at the trough; a window display exhorting passersby to have “Fun in the Sun”; and a graveyard of once-illuminated signs from defunct businesses—a museum of capitalist ruin.

My intent was not to document or interpret, but simply to fill a couple of idle hours on a hot summer day. Looking back, I realize that I assumed these photos would either function as art objects or not at all. When I picked up the developed prints at the drugstore, I found them only mildly interesting and tucked them away with the rest of my photographs, where they lay forgotten for decades. Having failed to function as art, they could only be read as documents—but in 1985 they could not yet operate as documents. They reflected the chronological present: the reality just outside my window. There was no contrast between here and there, between then and now. They were pure presence. They revealed nothing that was absent. They bore no obvious historical pressure, only the hint that the moment they captured was precarious, about to shift, transform, and collapse. For these reasons, they were archivally mute.

Looking at them now, forty years later, the photographs resonate in a very different way. The ancient Greeks distinguished between chronos, linear time, and kairos, the right or opportune moment. For these images, kairos arrived when their referents disappeared or mutated. Not only the specific buildings and streets, but the penny gumball machine and the cigarette advertisement represent forms no longer recognizable in the present. The viewer’s horizon of understanding has shifted. Many of the systems and the assumptions these images presuppose have collapsed or reconfigured into something else. It is only through this contrast—between then and now, here and there—that the images’ archival potency, and even their eloquence, becomes apparent.

In the forty-year gap between their creation and the present, these photographs did not become more beautiful, or even more interesting. What they became was legible in a way they were not at the time. Legibility, however, is subjective, and there is a risk they might be approached nostalgically. The nostalgic gaze treats the loss of the past with longing and sentiment. The archival gaze treats distance and loss as the necessary reagents to activate these photographs into a state of interpretive readiness.

When I went for that walk in 1985, I didn’t set out to create an archive, or to document anything at all. A bit of mid-summer boredom prompted an open-ended experiment. The rest was accidental. While standard definitions of the archive emphasize formality, authority, and control, much archival material comes from similar unintentional acts. Countless photographs like these lay dormant in closets, attics, and basements before eventually finding their way to yard sales, second-hand shops, and landfills. Separated from their original contexts, these memorials to the forgotten and inconsequential are simply awaiting the observer who will begin their process of activation.

But where do we go from here? The photographs, once silent, now signal that they may be important—not because they are beautiful or rare, and not because I intended them to be. I cannot say that I fully understand what they reveal. As their meaning has shifted, so has my role: from photographer to custodian. I will leave their interpretation to others. I can only care for the images and release them from storage into the present. For the moment, that’s enough.

—Stephen Canner

Hello Stephen, that was very well written, and our own personal history will be with us forever as memory or as photographs, whether we share them or not. My early years and into the latter part of the film world before digital, I used medium format and large format cameras (4×5), and only a few images at a time as to not waste film, but I have to admit, the newer digital cameras are sooo much better. My newer digital OM (formerly Olympus) has an ISO setting of 104,200 ISO! I have used 12,800 ISO for low existing light and no noise. Take care Ray.

LikeLike